Why it’s time for a Hopkins revival

- May 23, 2017

- 3 min read

Here’s the text of a blog I wrote for Foyles on why next year’s centenary of Hopkins’ first publication will be an excellent time to remember him.

Even though she appears mostly offstage, one of the most significant characters in Muriel Spark’s post-war novel The Girls of Slender Means is Joanna Childe, who teaches elocution in the home for young ladies where the tale is set.

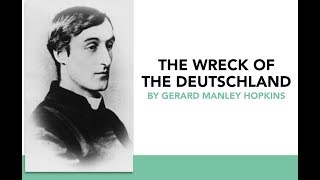

Poetry is her guide, and everyone in the house can hear as she beats out the stresses and throbs of Gerard Manley Hopkins at full volume. When she moves on to Wordsworth, it’s a let-down. “I wish she she would stick to The Wreck of the Deutschland,” sighs one resident. “She’s marvellous with Hopkins.”

It’s hard to imagine any such conversation nowadays. That’s partly because our modern domestic soundtracks are mostly musical rather than poetic. But Hopkins himself has also fallen out of fashion.

With the centenary of his first publication due next year, I hope that may be about to change.

Gerard Hopkins – he did not commonly use his middle name in his own lifetime – was born in Stratford, East London in 1844. The eldest child of a shipping insurer, he was a small, earnest young man whose chief concerns at Oxford were religion and poetry.

The university was the centre of High Anglicanism – a controversial movement in the second half of the 19th century – but Hopkins committed the ultimate rebellion for a young man of his day by “going over to Rome“.

He was formally received into the Catholic Church in 1866, yet even that was not enough. Set on becoming a priest, he joined the Society of Jesus, a hardcore order regarded at the time as a dangerous cult. It would set him apart from his family and university friends for the rest of his life.

While his order frowned on such things, he toiled privately composing verse in a radical system of metrics of his own devising. His most ambitious work was inspired by a tragic sensation of the day, when a ship carrying German emigrants to America – including five nuns – was wrecked in the mouth of the Thames.

Unfortunately, with its complicated syntax and unconventional form, it baffled all who saw it and his attempts to get it published in the Jesuit monthly journal failed.

Hopkins died of typhoid in 1889, aged just 44, with virtually nothing published. It was not 1918 that his university friend Robert Bridges – by that stage the poet laureate – published a collected edition. By the wartime years, Hopkins was regarded as a visionary genius – one of the finest 20th century poets the 19th century had ever produced.

I first encountered him at school and was baffled with the best of them. But something struck a chord and I found myself coming back again and again in adult life. However hard the writing might be to understand, Hopkins’ pent-up passions were easy to see in the frenzied repetitions and climaxes of his verse. I came to think of him as a poetic version of Van Gogh.

My new novel The Hopkins Conundrum follows the comic fortunes of a modern chancer who hopes to exploit the difficulty of Hopkins’ work to make his own fortune: he wants to convince the credulous that the poems contain the secrets of the Holy Grail.

My character’s madcap scheme to stir up Hopkins mania is entirely cynical, but I hope my comedy may generate an interest in this neglected poet for rather better reasons, and introduce a new generation to his rich, enthralling work.

Comments